Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Fire

If you don't like the US-led world order, wait until you see the alternative.

The talk of the foreign policy smart set for the past week has been the apparent anti-American turn from many of America’s longest-tenured allies. This can more charitably be described as a push for strategic autonomy from the United States, creating some distance between what Washington wants and what our friends are willing to do. That is not in itself a bad thing; both sides of the relationship have been pushing this in one form or another for nigh-on two decades – in the case of the French, that process pretty much started in 1945. Since the end of the Cold War and through the beginning of the 21st century, the script has basically gone like this: Washington wants everyone else to contribute more to their own defense, while everyone else wants to distinguish themselves from the United States and alter America’s traditional leadership of the alliance. Taken as a means of improving the transatlantic relationship, these sentiments are welcome; taken as a means of undermining it, they are not.

The recent push away from America was exemplified by the annual World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, Switzerland, where leaders from across the global political spectrum gathered and spoke. The talk of that elite conference was the supposed unreliability and hostility of the United States, forcing those who have historically been our friends to look elsewhere for protection, trade, and partnership. The main expositor of this view was the prime minister of Canada, Mark Carney, whose speech on the subject was met with gushing praise by the liberal pundit class, both here and abroad. In that address, he discussed how American behavior under Trump had caused a “rupture” in the international system that requires middle powers like Canada and Europe to chart their own course and find alternatives to a potentially hostile Washington. A lot was made of the purported death of the international order, including via an absolutely tortured analogy to Vaclav Havel’s greengrocer.1 But very little was made of one of the primary culprits of said dissolution, the People’s Republic of China.

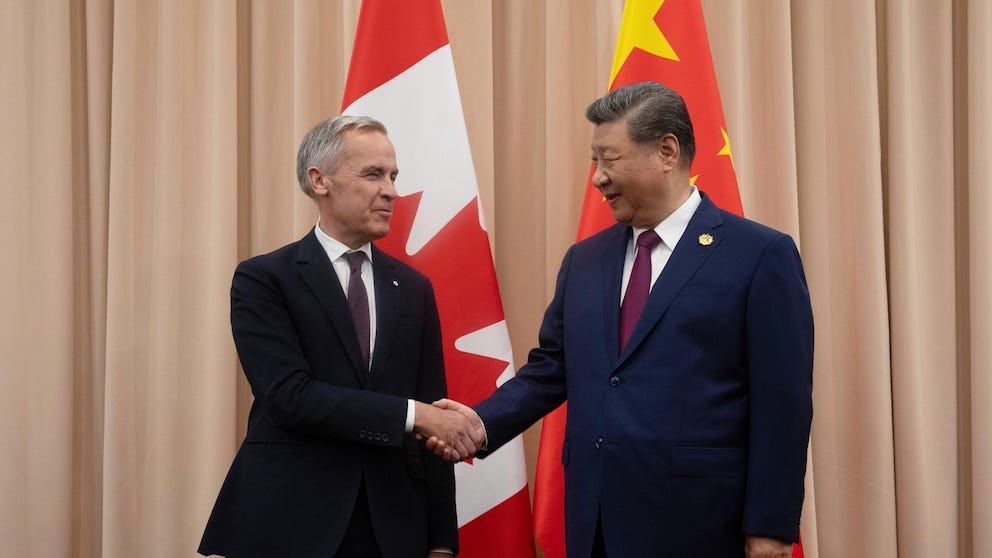

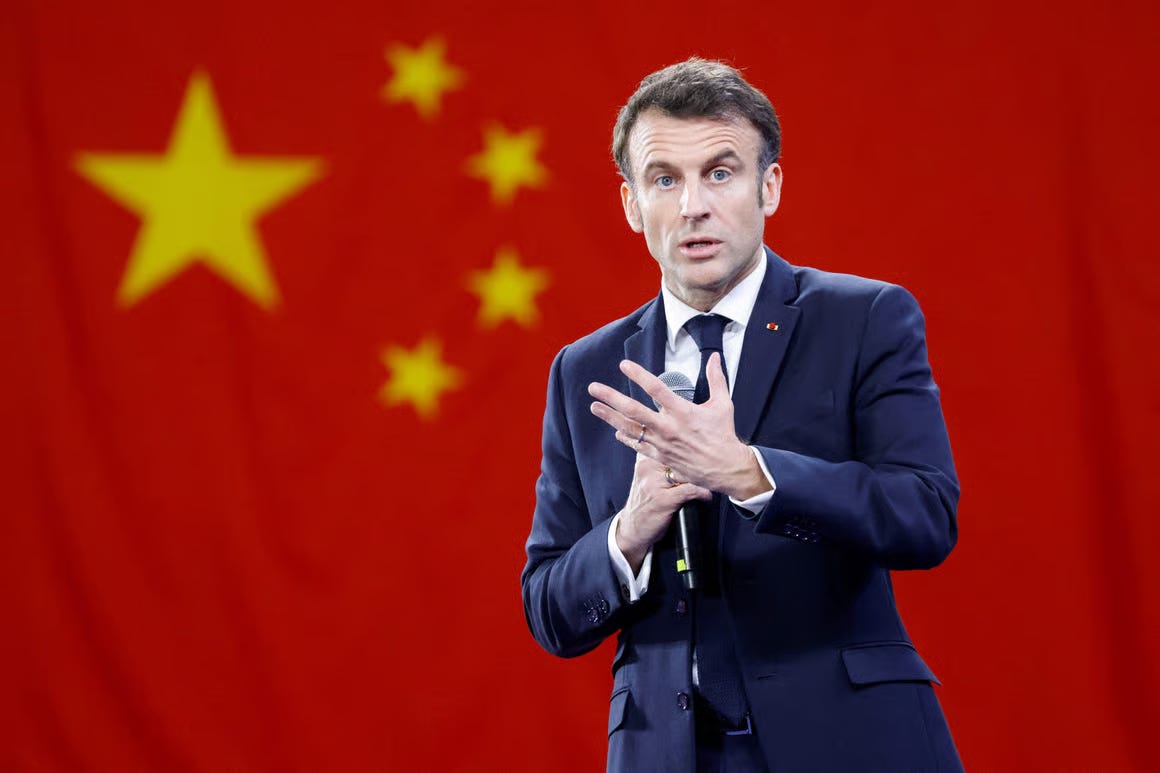

That characterization isn’t entirely true. Many of the leaders of these newly autonomous Western democracies did mention China. However, they did so not to blame Beijing for undermining the world order, but to praise it as a potential strategic partner and fount of stability. French president Emmanuel Macron was an exemplar in this regard, outwardly calling for more Chinese investment in key European manufacturing and technology sectors and welcoming a closer relationship with Beijing. Carney was similarly solicitous, if less obvious about it while at Davos. Yet he was not at all shy about it the week or so before, when he made a pilgrimage to China to pay tribute to Xi Jinping and grovel at the feet of the Chinese Communist Party. During that trip, Carney announced a new “strategic partnership” with China that would more tightly integrate the two nations economically – in practice, this means making Ottawa subservient to Beijing. Other allies have fallen into this trap as well, notably the British under Keir Starmer’s Labour Party. In just the past year, Labour has tried to cede critical American military bases to a satrapy of the CCP, said it would not choose between America and China, and approved a massive new Chinese espionage center – sorry, embassy – in the middle of London, conveniently placed right alongside critical government communications infrastructure.2

Naturally, Chinese propaganda networks amplified these anti-American sentiments broadly online. They have everything to gain and nothing to lose when America’s friends start to sour on Washington and sweeten on Beijing. Unlike the Chinese, though, those putative allies have a great deal to lose. Because although particular American leaders may be hostile to them, China is certainly hostile to them. Shifting allegiances is not ‘balancing’ or engaging in ‘optionality’, it is giving a civilizational enemy the keys to the kingdom.

To be clear, the second Trump administration has done a bang-up job of alienating and attacking our NATO allies over the past year. The White House has levied tariffs against them, minimized their military sacrifices, slammed them over their speech and migration policies, favored Russia over Ukraine in key moments, belligerently tried to coerce Denmark into ceding Greenland, targeted Canada with annexation talk, and hurled many more such slights, insults, and antagonistic policies their way. There have been some exceptions, but the overall policy from Washington to Europe and Canada has been, at the very least, unfriendly. This is unnecessary, counterproductive, and wrong. This approach does not improve the relationship, nor move our allies to align better with our interests and priorities. These threats are unbecoming and detrimental to a longstanding alliance that was never purely about convenience, but based on shared values, goals, and threats.

At the same time, these are the actions of a mercurial, easily-flatterable, fairly non-ideological president who is term-limited and will be out of office in three years. Trump himself is so sui generis that his approach to foreign policy is essentially irreplicable. Some in the MAGA movement are driving this anti-NATO push, but they are not guaranteed to be the successors to this president. Hell, given how the term is going so far, it may very well not be a Republican at all who follows Trump in the Oval Office. Additionally, half of Trump’s threats are just him trolling for anger and trying to whip up drama. That is not to excuse them – doing so for such a puerile reason is bad enough on its own – but to explain why they may not be the existential threat to NATO that some breathlessly suggest. Trump, even if he wanted to, could not unilaterally order the dissolution of the Atlantic alliance, nor could he repudiate mutual defense treaties on a whim. Congress these days is quite supine, but it is not nonexistent. In short, the problem here is limited and solvable: either just wait the buffoon out or change your approach to one of flattery instead of confrontation. Even without giving him any tangible wins, he’ll embrace them as personal triumphs. Our adversaries in Moscow and Beijing seem to have internalized this reality; it is time that our friends in Paris, Ottawa, London, and Brussels do too.

Instead, they’re choosing to cut off their nose to spite their face. No matter how potentially hostile a singular American president can be, the response cannot be to leap into the waiting arms of an actually hostile power, one that desires nothing less than total submission. China is not a potential strategic partner for Europe or Canada. It is an enemy of the West that will not stop until it becomes the world hegemon, reclaiming what the nation believes is its rightful position at the very heart of international affairs. Our NATO friends naturally have a different geopolitical calculus than we do when it comes to the problem of Beijing: none are a Pacific power, none are the primary world power, and none have the mutual defense pacts or military presence we do in the region. They view China as a growing economic powerhouse with a high-tech, sustainability-centric manufacturing base and a level of political predictability, albeit recognizably imperfect in the details. They see China not as an aspirant to the throne of international politics, but as a superpower that could be dealt with as an equal by the European Union, engaging in mutually beneficial transactions, all while taking America down a peg. In a more Chinese and less American world, they believe that Europe could reclaim something of its former preeminence as a leader of the West.

This is a fatal misunderstanding of what the Chinese Communist Party is, what it desires, and what a Chinese-led world would look like. The Europeans and Canadians would not be able to live in the functional equivalent of a museum, fat and happy in their generous welfare states and protected by an American nuclear umbrella. They would instead be vassalized by an aggressive Beijing that seeks to turn those Western nations into subservient tributaries with little in the way of autonomy or power. China does not seek partnership, but submission. This is eminently clear in the way that Beijing has acted over the past decades, ramping up under the dominion of Xi Jinping. It has routinely and egregiously violated all the rules and norms that our friends say they value so highly and that they are worried that America might violate in the future. China is actively committing genocide – a real one, unlike the bogus Gaza genocide claims – steals intellectual property, manipulates its currency, seizes the territory of its neighbors, harasses foreign civilians, operates a totalitarian police state, unleashed the Covid pandemic on the world, violates all manner of international law, and bankrolls and supports the evilest regimes on the planet. (I could go on, but that sentence was already near-interminable.)

If that’s not enough to convince the Europeans that they’ll eventually also be in the dock, there’s the matter of history. The Chinese Communist Party and Xi Jinping in particular are obsessed with rectifying what they perceive as historical wrongs. That impulse has primarily been targeted toward territorial revanchism to restore China’s most expansive historical borders, notably including the planned forced ‘reunification’ with Taiwan. It is already in the process of subjugating and eliminating the independent political and religious traditions in Tibet, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Hong Kong. But China claims other lands that sit outside of its borders, too. It believes it should own the entirety of the South China Sea, various outlying Japanese islands, significant swathes of the Russian Far East, chunks of India, parts of Pakistan, and sections of Mongolia and Vietnam.

These territorial ambitions are evidence of the CCP’s long historical memory, incorporating events that happened long before it came to power in 1949. Europe does not need to worry about this aspect of Chinese historical revisionism. It does, however, have to worry about Chinese vengeance for events that happened two centuries ago. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, European powers treated a declining, stagnant, insular Chinese Empire as a playground for imperialism – a land ripe for partition, exploitation, and improvement. This involved forcing painful treaties on the Chinese government, sparking multiple armed conflicts, carving out territories somewhat akin to feudal fiefdoms or demesnes, and generally turning a once-proud nation into a subservient, yet still populous and increasingly productive, satellite of the European empires. In China, this is known as the ‘Century of Humiliation’ and it has become a central point of the regime’s historical narrative. As such, the CCP wants to reverse the roles foisted upon it by the West of the past. That means forcing Europe into its own ‘Century of Humiliation’ as punishment for upending the only correct way the world should be oriented: with China powerfully at its center.

The Chinese Communist Party does not seek friendship with Europe or Canada. It does not want to be strategically aligned for mutual benefit. It wants to destroy the regnant world order, impose its own vision of power on the remnant, and reverse what it sees as historical wrongs. This is not a power that can be appeased, worked with, or balanced against. It is an existential danger to Europe as it sees itself today. And yet it is perceived by its prey as an actual alternative to an admittedly-frustrating and inconstant America. This is not just naïve, it is dangerous.

No matter how implacable and antagonistic the US may be, our politics can and will change. That is the nature of a fractious, representative democracy. Our foreign policy will ebb and flow similarly, leading to periods of tension and release. That is a normal cycle for a geopolitical partnership, even if an uncomfortable one at times. But there is always the inevitability of reaction, removing the strain and strengthening the partnership. When it comes to China, there is no unpredictability at all. Europeans and Canadians have no need to parse internal politics to see which party is more favorable at any given point in time; China is very clear where it stands and speaks with one voice. It is also an implacable foe. Nothing will change that except submission. Unfortunately, by aligning with Beijing as a counter to a temporarily-Trumpian Washington, our friends are jumping out of the frying pan and directly into the fire.

The international order is not dead, despite what the snobbish elites of Davos might think.

And yes, there are actual secret rooms in the bowels of this planned facility that sit directly adjacent to the communications cables that carry much of London’s financial data and British government information. It sounds right out of an Ian Flemin novel, but it is all too real.