The Wonders of Modernity

Despite the constant criticism, we should all be immensely thankful to be living in the present.

Like many Americans, I tend to find myself pondering over gratitude at this time of year. Whether that is sparked by the increased presence of friends and family, the Zen-like process of preparing a delicious shared meal, or merely an attempt to come up with something good to say at the Thanksgiving table, appreciation is on my mind. Of course, my mind goes first to the personal: my wife and daughter, my family in general, my loyal (and loud) chihuahua, my friends. Then come more general things like (relative) health, prosperity, happiness, and career success. But once I’ve bounced these more typical thoughts around my head for a bit, I continuously return to one broad idea: the glories of the present.

That may sound odd coming from a historian, but I feel it deeply. I adore the past about as much as it is possible to. My office is adorned with historical maps, posters, books, and tchotchkes. My favorite novels are in the public domain. I name houseplants after nineteenth-century British politicians (I’ve got Lords Balfour and Salisbury already). I could probably sink the Titanic (well, maybe the S.S. Minnow) with the number of history books I own. I have busts of both Napoleon and Wellington. I think about the Roman Empire every day.

But I firmly believe, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that today is the best possible time for a human to be alive. Not only is the 21st century an incredible time to be a member of homo sapiens, the past was far, far worse to live in than most people can imagine. Let us count the ways.

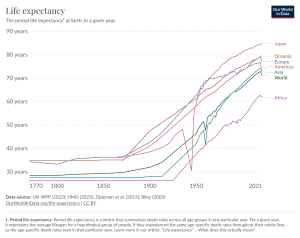

The best place to start is to look at the big picture statistics on the most important measurable factors for a good life: longevity and prosperity. Both of these have massively improved since the dawn of the modern era, especially in the past 150 years or so. Life expectancy, which is obviously an extremely important indicator of overall quality (and quantity) of life, has dramatically increased across the world since the early 1900s. This trend has brought average lifespans at birth from between 30 and 40 years in 1875 to between 70 and 80 years for most of the world today. Doubling the length of time that the average human lives is an accomplishment of a magnitude that is nearly impossible to comprehend. The wealth of experiences that humans are now able to collect allows us fuller, more productive, happier lives. This is the product of modernity – medicines, genetically-modified foods, sanitation, electricity. Not only that, but people today die far more peaceful deaths than did our predecessors. The rate of violent death has collapsed dramatically over the course of human history, while treatable illnesses no longer take myriad lives through intense pain. The pessimists, however, would say: “Just because people are living longer, that doesn’t necessarily mean their lives are better.” That’s a good point.

Fortunately, global prosperity has radically risen since the mid-19th century. For the vast majority of recorded history, global GDP was stagnant; this changed spectacularly with the Industrial Revolution. In the past 50 years alone, world affluence has more than quintupled, and this durable trend shows no signs whatsoever of slowing down. Well, the critics say, what about inequality? Aren’t those benefits entirely concentrated at the top? Not even close. In 1820, nearly 80% of the world’s population – which, remember, was far smaller than it is today – lived on an inflation-adjusted equivalent of less than $1.90 per day. That is the definition of extreme poverty, which inevitably leads to malnutrition, disease, and, ultimately, preventable death. Today, less than 10% of mankind lives in such squalid conditions. Two centuries ago, less than 1% of humans lived on more than $10 per day; now, that figure is close to 40%. That change is nearly unfathomable. The living standards we see as middling today would be mind-bendingly wealthy across most of the world, even in the recent past.

Okay, but what about the marvels our ancestors built? Is this very large Twitter account right when it asks “Why did human beings stop building wonders?” No, that account and the ideological position it represents are completely wrong. In fact, they are blind to the true wonders of our modern era. A bit of historical perspective would do them good.

Mont St. Michel, the glorious architectural site whose image graces the beginning of this article, is undoubtedly amazing. I cannot wait to eventually see it in person. And therein lies the wonder of our modern age. Not only do I know a significant amount about a site in France, thousands of miles and one major ocean away from my home, I have seen photographic reproductions of it and videos of the place itself. After viewing those magical depictions of a place so far from my residence and reading about it on the Internet, I can buy a ticket for a plane which will literally take me into the sky and deposit me several hours later in France, where I can take a train or an automobile to see this beautiful locale in person. When Mont St. Michel was built in the Medieval period, it is unlikely that anyone outside of the immediate vicinity knew about it or would ever have the opportunity to see it in person. Most people could not even read about it, as they were largely illiterate and manuscripts were rare (the printed book would not be popularized for several hundred years). Now, for the product of just a few days of work (based on the statistics above) the grandeur of this French citadel is physically accessible to most; with the ubiquity of the Internet, it can be viewed by billions.

Well, sure, people can see these amazing relics of the past better now than they used to. But we still don’t make things of equivalent beauty or wonder, right? Wrong. Take a gander at any large modern city around the world and you will see marvels that would be considered downright miraculous by humans of the past. Glass windows – and the natural light they allow into interiors – were historically the preserve of the rich, and even they could only have so many without creating structural issues or breaking the bank. Now, entire cities are composed of buildings covered almost entirely in transparent glass, while normal homes are filled with natural light during the day and plentiful artificial light – without the smoke or haze created by flame – at night. We are still building miraculous things all the time: we have multiple telescopes floating in space to observe the origins of the universe, we have nuclear-powered warships that can remain underwater nearly indefinitely, and we just built an entertainment venue in Las Vegas that would make any Medieval man fall to his knees in awe. Humans are transported around the world via the magic of flight, rail, or road transit; streets are clear of that formerly omnipresent product of pre-modern transportation: horse manure. Hot and cold are mere inconveniences, as air conditioning and heating are cheap and accessible, including in said forms of transit. Fresh potable water is pumped directly into our homes, while our waste is pumped out.

Our everyday lives are the preserve of ancient fantasy. Within mere miles of our homes, we have supermarkets that are full of the foodstuffs of dozens of nations, which have fresh produce regardless of season and fresh meats and seafood in abundance. The aisles of a modern grocery store would impress the richest humans of even a century ago; their minds would be blown when they understand the incredible journey many of these products went on to get to the shelf. The accessible prices would be entirely unbelievable. And almost none of us have to grow this food ourselves. In fact, gardening is now merely a hobby; for millennia, that was called subsistence. Our kitchens have technology that would be literally unbelievable to our forebears. Gas stoves, refrigerators, freezers, and, of course, microwaves, are astounding creations that would be viewed as magical centuries ago. Sitting in the depths of our cabinets, we have a literal king’s ransom in spices. The drudgery of housework – something which took up the vast majority of time for one entire half of the population – has been almost eliminated, saving enormous quantities of time and freeing up women to use their God-given talents to better society. Washing machines, dryers, and dishwashers are incredible innovations; hell, we even have robot vacuums!

No single product makes the wonder of modernity clearer than something we all seem to take for granted, if we don’t outright despise it: the smartphone. Since the early proliferation of the computer in the 20th century, processing power has vastly increased while decreasing immensely in size. What now fits in our pocket would fill several rooms in 1950. Even since the advent of the smartphone/PDA in the late-1990s to mid-2000s, the advances have come in leaps and bounds. Not only are we able to store gargantuan quantities of digital information in a smaller form factor, we can access the Internet at extreme speeds, take photographs that rival professional cameras from only a decade ago, and view and transmit live video across the planet instantaneously. In our pockets, we have access to more information than could fit in the Library of Alexandria a hundred times over, instant translation of any language, the ability to bank, invest, and pay for goods, and the potential to communicate with any of the billions of other humans on the Earth. Even the world’s poorest people have access to this life-changing technology.

And yet we take this for granted. People of all political persuasions argue that we live in a dystopia, that the past was better, and that the world today is full of nothing but poverty and dread. Those on the left believe that the scourge of capitalism/neoliberalism/America has created an existence filled with horror and oppression; those on the right aver that our present is debased, backwards, and meaningless compared to prior epochs. Both of these groups idealize their preferred alternative – the utopia of fantasy or the perfection of the past – while denigrating the present. But they’re both profoundly wrong. We live in the greatest time to be a human that has ever existed. Our daily lives are so much better than those of our ancestors that it is hard to fathom. Today’s average man has a richer, healthier, and more enjoyable life than did the monarchs of a few centuries ago. If any of our great-grandparents were plopped into 2023, they would be staggered at the success and luxury of our age. If we ventured back further in the past, the shock would be even more palpable.

In short: Modernity is great, actually. The problem is that our culture no longer has the ability to recognize and celebrate that fact. This Thanksgiving, the wonders of the present age are something we should all be grateful for. Our forefathers certainly would be.