On American Interests

The defense of American national interests is the lodestar of foreign policy. But what are those interests? The answer to that ever-pertinent question defines our future.

Discussions of foreign policy invariably come back to one thing: American interests. Advocates for all sorts of divergent approaches to the world center the idea of our national interests as the basis for their preferred policies. No matter the idea, from full-on isolationism to interventionist Wilsonianism, the advocate declares confidently that said policy is the best or only way to advance or defend American interests. The problem is that these interlocutors rarely, if ever, define what those interests actually are. And that definition is the most critical thing when discussing foreign affairs and Washington’s interest in them. Not only is that question of paramount importance in defining different worldviews across parties, but it has become increasingly crucial to understanding the major foreign policy schisms that characterize the political right in 2025. Without a proper definition of what our national interests are overseas, commentators end up talking past one another and failing to come to agreement on even the basics.

Some view our interests abroad as parochial and local, relegating the concerns of far-flung continents and countries to the back burner and favoring immediate domestic concerns. Others see the happenings in every nation on Earth as being intrinsically our business and identify America primarily with the global community. The former position advocates for withdrawing from the world and creating a Fortress America, so to speak. The latter position pushes American intervention to solve every problem, even if totally internal to a foreign land. Both sides would say that their prerogatives are the only way to safeguard or defend American interests, and each would be correct under their own definitional structure. In reality, however, neither is right. American interests are broad, yet not universal. They are focused, but not myopically so. They encompass a range of nations and their external activity, but not every single country’s internal politics.

To properly comprehend American interests in the 21st century, we must take a trip into our shared past. The evolution of what our interests are, correctly understood, is told through the process of American history. As our country has changed and grown, so have our interests in foreign affairs. This is an accretive process, where the national interests of the past continue into the present, supplemented by further additions along the way. The world of the Early Republic is dramatically different from the world of 2025; our place in that changing world has also shifted. Revisiting our history is the best way to gain insight about the fluctuating nature of America’s interests and role in the world at large, as well as to understand what those should be today and into the future.

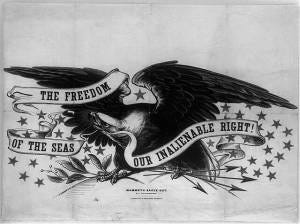

When the United States was founded, it was a relatively small merchant republic that barely extended past the Appalachian Mountains and was largely a producer of raw materials for export to European empires. In the first few decades of our national existence, our interests abroad were relatively minor – namely, the protection of neutral rights, unmolested seaborne trade, basic domestic security from invasion, and the consolidation of the new republic from European imperial revanchism. Our success in defending these interests was decidedly mixed. We successfully fought wars for the protection of commerce against the Barbary pirates, while also pushing hard for our European brethren to respect American trade as a neutral party to the conflicts that devastated the continent through the late-18th and early-19th centuries. Unfortunately, that resolute defense of mercantile neutrality led to us being invaded by our former colonial masters, who proceeded to raze our capital. You win some, you lose some. As Europe recovered from the decades of existential conflict unleashed by the French Revolution, America was able to consolidate its existence as an independent polity, integrating the new lands purchased (or taken) from fading and distracted foreign empires. By the 1820s, Washington was brimming with self-confidence and incorporating the novel reality of the Latin American anti-colonial revolutions into its foreign policy worldview. This produced the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, a turning point in America’s relations with the world.

After the publication of that strongly-worded presidential decree, boldly claiming that the Western Hemisphere would henceforth be free from external imperialism, America became more assertive in its global role. The defense of Latin American revolutions from European interference was not a core interest of pre-1823 America, but it quickly became one as our nation expanded in size and influence. The period between the Monroe Doctrine and the Civil War, lasting nearly four decades, saw American interests expand concurrently with the growth of the country itself. At this stage, our interest in trade and export became even more critical, as the industrial and productive economies vastly improved with the settling of the West and the advance of manufacturing. We sought access to global markets – including opening Japan by force – and a greater ability for Americans to achieve our aims of domestic security and prosperity. That entailed gaining a greater degree of hemispheric control and becoming a true geopolitical power. Aggressive expansionism was the way to do this, and antebellum America was highly successful in that proposition.

After the Civil War ended the pretense of separatism within the United States and forged a stronger Union, American foreign policy settled into a general rhythm, where the nation was the undisputed regional hegemon and was able to exercise a high degree of local influence, even in the face of more powerful European states. At this point, our interests expanded to promote our industrial dominance and innovation across the globe. We consolidated our continental possessions and began making inroads to further expansion throughout the region. To this effect, we purchased Alaska, favorably settled boundary disputes with our neighbors, and laid claim over myriad outlying islands of general maritime strategic importance. America continued its policies of market access, broad-based global trade, and an economy geared to exporting our wares throughout the world. The US was more focused internally during this period than others – building infrastructure, dealing with the aftermath of civil war, and fully peopling the West – but it remained a major player in global affairs, particularly in the Western Hemisphere and its environs.

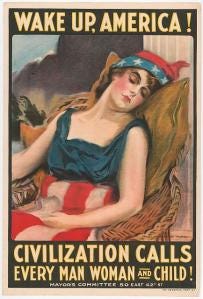

The critical period in the shift from a regionally-focused power to a globally-focused one came in the half-century between the 1890s and the end of the Second World War. In that stretch of time, the United States truly became a world power on par with the greatest geopolitical actors on the planet. The rapidly increasing commercial and industrial might of America necessitated further trade, market access, and integration into the broader global security apparatus to defend those economic interests. At this point, America was one of the greatest beneficiaries of the 19th century world order, building immense wealth, a sizable population, and a profound degree of domestic security on its back. That also made the defense of that order writ large into a core American interest, requiring an active presence overseas. This was the era of American expansion into foreign theaters like the Philippines and the South Pacific, the development and annexation of the Panama Canal for the safeguarding of hemispheric commerce, and the large-scale projection of American military power far afield. Defending the world order from the threats seeking to upend it – and thus disrupt American success – embroiled us in two world wars, but simultaneously allowed us to usurp the British Empire and become the world’s predominant superpower. Still, we retained our hemispheric interests and enforced them, including multiple invocations of the Monroe Doctrine against powerful European states.

After the triumphant end of the Second World War, America was ascendant among our peers in the developed West. Europe was wracked with the devastation of two existential conflicts, the immediate consequences of an epochal, continental genocide, and the specter of totalitarian communism standing menacingly behind the Iron Curtain. Washington was comparatively unscathed and emerged from the war as its clearest victor, assuming the mantle of leadership over the free world and contesting against the Soviet challenge to that system. Becoming one of the two recognized global superpowers and the only one promoting the maintenance of the extant world system gave America an unprecedented ability to set and enforce the worldwide rules of engagement on security, commerce, and more. It helped us defeat the threat posed by Soviet communism – including in our own hemisphere – and has buttressed our geopolitical status ever since. The period of nearly 80 years since the dropping of the atomic bombs has been one of the most successful in the long history of human civilization, seeing dramatic and broad-based increases in life expectancy, living conditions, material prosperity, and global peace in both the United States and the world at large. Maintaining the global system as it currently exists – an extremely broad thing – is the paramount interest of America abroad, which is a dramatic shift from the parochial interests that befitted our nation in the Early Republic.

Looking at our history, one can see how dramatically our conception of the national interest has expanded since the ratification of the Constitution. Although that particular evolutionary process informs our understanding of the national interest today, we cannot solely look at our own history as an example. In fact, the polity most analogous to present-day America is not American at all; it is Britain, particularly during the heyday of the Empire: the 1870s through World War I. This was the last era of one truly dominant power setting the rules for the global system, which is the closest analog to modern America. Just as with Britain at that time, our interests are truly world-spanning and the abnegation of any of them would deeply impact all of them; the destiny of America, as with Britain, is tied directly to the stability and continuation of the extant world order. That order, one of unfettered maritime commerce and open sea lines of communication and trade, is only secured by widespread peace, especially between major powers. That has been the case for the past several decades, but it is becoming increasingly precarious. Just as the British in the early 1900s, we face a rising set of enemies who seek to upend the global order and replace it with something more favorable to their interests. Britain had Germany and its abettors, we have China and its axis of revanchist authoritarian states. The British Empire fought a world war to defend that order against its detractors in 1914, in an attempt to safeguard the prosperity and freedom Britons reaped from their geopolitical position. We should hope not to follow that same path, but succeed in another way: acting proactively to advance our national interests and resolutely face down our foes.

As we have seen, our interests are extensive and reach nearly every corner of the world map. This was a natural evolutionary process for a maritime merchant republic that sought to become a geopolitical power player; at first, you simply play by the rules others have laid out, then you assume more responsibility for defending the system you enjoy the spoils of, and finally, if all works out well, you end up making the rules to your advantage. That is where Washington finds itself in 2025 and it is a position well worth defending given the astoundingly positive results.

There are some who see our role as a world power as a net negative for America and Americans, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. Our rise as a geopolitical power has coincided with an immense expansion in the living standards, relative income, and life expectancy of the average American. Material progress has been stunning and individual freedom has rarely been better. Those who wish to withdraw from the world to focus only on domestic concerns, especially cultural ones, miss the forest for the trees. Without America’s dominant position in the world system, our domestic situation would be far more parlous. We would be poorer, less safe, more fractious, and could actually go into something like the terminal decline critics suggest we are already mired in. Ironically enough, the ability to focus inwardly is itself a product of the prosperity and stability provided by American leadership abroad and a signal of our strength as a nation. We have many internal problems, but the solutions do not lie in global withdrawal; that would merely make those issues intractable.

If we are indeed committed to global power – which, as has been detailed, has been extremely good for Americans – what does that entail? Does it force us to intervene in every single dispute as arbiter, as many of the critics of this role suggest? Not at all. The threat to our interests does not come from any and all conflict, but from large-scale fighting that directly impacts a friend, ally, or state to which we have given security assurances. The avoidance of that sort of conflict is paramount to American success. Deterrence of such damaging warfare is the best way to ensure the protection of American interests in global trade and free commerce; credible deterrence requires a commanding military that is forward-based and a leadership class that is comfortable using it if necessary. This is why we have historically fought against nuclear proliferation among unstable states and non-state actors, why we have stationed American forces around the world to bolster the defense of our allies, why we have engaged in defensive alliances with friendly powers, and why we have the globe’s most powerful fighting force.

Those alliances, oft-lambasted by the right-wing critics of American foreign policy, are immensely beneficial to us. They allow us to exert a degree of constraint over the policies of other powerful nations, aligning them with our vision of the global order instead of pushing them into the eager arms of our foes. These agreements also ensure a broader peace, whether in east Asia – look at the enmity between Japan and South Korea that has been defused by American relations with both nations – or, in fact, in Europe. NATO, easily the most unfairly maligned alliance in the present political discourse, has been a godsend for American interests, particularly in the post-Cold War era. The 80 years of peace on the European continent that have been fostered by this alliance are unprecedented in modern history; in spite of the present war in Ukraine, the continent has not seen this long a stretch of widespread comity since at least the Reformation. NATO has its share of problems, from inadequate defense spending by many of its long-time members to the mission creep evinced by its involvement in Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. But these are rectifiable and, in the grand scheme of things, relatively minor given the success of NATO’s primary mission: securing European peace.

That peace has been severely threatened by recent events. America’s enemies – notably Russia, Iran, China, and their respective dictatorial satraps – are on the march. They have taken advantage of the weakness displayed by the Biden administration’s abandonment of Afghanistan and its generally conciliatory foreign policy, fomenting international strife and engaging in wars of extermination against American friends. These powers seek a return to the past where America was far too self-involved to engage actively with the world. In their own way, they mirror the desires of the domestic retrenchers, pushing for a world where each regional power is able to effectively carve its area into hard spheres of influence where they exert dominant control, removing the US from the equation and dramatically shifting the nature of global security. For the future success of the United States, we must ensure this cannot happen. That does not mean putting American boots on the ground in every nation this side of Beijing, but it does mean acting in meaningful ways to promote our interests and ensure deterrence of broader conflict. Sometimes, as in places like Germany, Japan, and South Korea, American presence is needed as a stabilizing force and an outlet for regional power projection, but this is not always the case, particularly in the modern threat environment. In our case, maintaining deterrence means forestalling conflict via intervention – often indirect – and punishing aggressors. We have two perfect examples of this in the current age: Ukraine and Israel.

In both situations, supporting the beleaguered power is in our interests; we should not wish to see either Russia or Iran triumph and extend their malignant tentacles across the whole of their regions. This outcome would increase the prevalence of conflict and the likelihood it would involve us directly, as well as disrupting important trade routes and partners. Aiding Ukraine and Israel is perhaps the easiest way to advance our interests and harm our adversaries without direct involvement. We merely have to provide weapons – purchased from American companies and providing American jobs – and diplomatic support and allow our friends in Kyiv and Jerusalem to do with that what they will. The bang for the buck that we receive through such simple actions is immense; just look at the shell that Tehran’s terrorist proxies have become, entirely through the actions of Israel alone. Now imagine what the world would look like today had we been even more supportive of Israel after October 7, allowing them to go hammer and tongs after Iran with our support. Or if we had given Ukraine the weapons and ammunition it required – without absurd conditions – when it could actually have made a battlefield difference. Such a world would be far better than the one in which we currently live, where two hot conflicts remain a live issue, harming our interests all along the way.

This is what those who seek a return to the myopic, parochial American interests of the past would gladly accept, even if they do not realize it: a more dangerous world where Americans are materially worse off. That is the price of retrenchment. And it is a price we should be entirely unwilling to pay. Our nation is not even remotely the same as it was in 1790, so why should our conception of the national interest remain static? Instead of seeking a return to a world that has not existed for over 200 years, we should embrace our global responsibilities and interests, defend them against the foes who seek to undermine the world system, and move toward a 21st century defined by America, not her adversaries. The United States is not the small, largely impotent nation we were in the years immediately following independence. We, correctly, do not wish to be that again. Our responsibility is to our progeny: to make America as strong and great as it can possibly be in the 21st century, not the 19th. That means assiduously defending our broad foreign interests as a world power. Anything less would be a dereliction of duty to the past Americans who fought for our current status and the future Americans who will surely benefit from us maintaining it.