Aligning Foreign Aid with Foreign Policy

Foreign aid is a cornerstone of American world power and must be properly revamped if we wish to win the 21st century.

Since the second Trump administration came into power last month, one of the biggest targets for the MAGA movement, via Elon Musk’s DOGE, has been foreign aid. The fact that the United States sends taxpayer dollars overseas for aid programs has long been a bugbear of some on the political right, with claims that it is universally wasteful, takes hard-earned money from Americans in need, and spends far too much of our tax dollars on useless boondoggles. These attitudes have been prominent for decades, but now they are getting a full hearing at the highest levels of the federal government. So far, the president has taken numerous actions to curtail it, from a near-universal pause on all foreign aid spending to the attempted closing of USAID, the executive agency tasked with delivering and supervising much of our overseas aid. Most recently, most USAID employees around the globe were placed on administrative leave, essentially making the agency nonfunctional, at least temporarily.

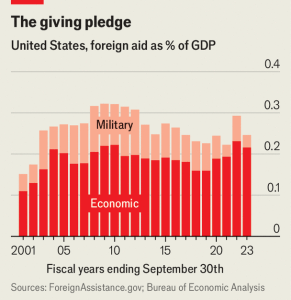

Proponents of the Trump administration’s actions have leveled several different arguments against foreign aid, some merited, others less so. Perhaps the least convincing is that cutting out foreign spending will save Americans money and help balance the budget. The issue here is that the entirety of our overseas aid is less than one percent of federal spending. We spend far more domestically and get much less for it; if those who say we need to reduce deficits are serious, they would look elsewhere first, namely at entitlement programs. Others, namely Musk himself, argue that US foreign aid, even when ostensibly for humanitarian purposes, is actually a front for American intelligence activities and, as such, should be shuttered. In actuality, this is basic tradecraft undertaken by every nation with a serious foreign intelligence program; plausible deniability and cover stories for covert actors are necessary, and having employment at legitimate agencies like USAID serves this important purpose well. Also, those who wish to have a strong and secure America – as most MAGA supporters claim to – should support such minor dual-use aspects of our foreign aid, as they provide us a window into major potential security threats overseas before they fully materialize here.

If these more spurious rationales are ignored, as many more serious backers of the aid freeze do, the case becomes better. These proponents of the freeze argue that it is necessary to stop all foreign aid, at least temporarily, to completely overhaul, if not end entirely, the way we send money overseas. They claim that there is a large amount of waste, fraud, and abuse, a myopic focus on progressive programming, and an inordinate funneling of money to left-wing NGOs that work hand-in-hand with the Democratic party. Much of this species of critique revolves around USAID, as it is the poster child for the issues raised. Let’s investigate.

USAID does indeed fund a plethora of progressive absurdities, including gender studies programs in developing nations, LGBT interpretive dance (yes, really), and DEI programming everywhere from Vietnam to Libya. These programs are wasteful and imperialist in the worst way – they are imposing radical values on traditional societies with no understanding of how the alienation that can cause negatively impacts our ability to promote the national interest abroad. But they are the exception to the rule when it comes to our foreign aid. Most of that spending is far less radical and far more useful; it supports important global health programs that reduce the likelihood of preventable disease outbreaks here in the US, it improves the lives of hundreds of millions of people in nations that are the prime theaters for geopolitical competition, and it promotes America as a force for good internationally. All of that is necessary for our future geopolitical success, which makes it all the more imperative to eliminate the aspects of our foreign aid program that undermine these positive expenditures.

Another major issue with USAID is the fact that a sizable chunk of its payments have gone to groups involved with designated terrorist organizations; the monies sent to areas in the Middle East and Central Asia are particularly suspect in this regard, as the “civil society” groups and NGOs that receive American funds are far too often cozy with Hamas, Hezbollah, al Qaeda, and others. The broader issue that is represented by this inadvertent (one hopes) terror financing is the general lack of accountability within our foreign aid bureaucracy. Audits, even when they are carried out, are toothless and have no visibility into the final expenditure of funds, merely the grants themselves. That is not how we should run a bureaucracy that spends billions annually, even if the overall spending is a fraction of the overall budget. This critique of our foreign aid system is right on the money. We should absolutely do a better job following where these funds go, work to make our spending more efficient and aligned with policy goals, and eliminate any and all funding for groups that have relationships with not only designated terror groups, but our enemies more broadly.

And that brings us to the progressive NGOs that USAID dollars fund. Far too many of the recipients of USAID dollars are left-wing nonprofit groups that have little accountability and boost the priorities of the progressive movement and the Democratic party. These organizations do not merely spend money for the express purposes of the federal government, but funnel funds to favored recipients, including progressive activists and political causes. The federal government is prohibited from this sort of explicit partisanship, but NGO cutouts use taxpayer dollars to achieve ends that the government is either unwilling or unable to. This is unacceptable. If we are to involve non-governmental organizations in the activities of the federal government, they must be heavily supervised, regularly audited, and explicitly nonpartisan. This is not the case as of today, and it must change.

There are serious problems with our foreign aid bureaucracy – namely the lack of proper oversight, the overreliance on left-wing NGOs, and the promotion of divisive progressive ideology – but we mustn’t miss the forest for the trees. Foreign aid is a key component of our soft power abroad and our ability to influence nations we seek to bring into our orbit or outside of that of our foes. Ensuring that it continues to flow in a manner that is consonant with American national interests is paramount to our ability to impact nations around the world. And this is where the critics have a point, even if they are going about the solution in a haphazard and unhelpful manner. We do need to reorient our foreign aid strategy and tactics to prioritize our national interests and deprioritize the enrichment of progressive NGOs around the world. But that requires reform, not revolution.

Far too much of the Trump executive action and the DOGE ‘auditing’ process has been chaotic and slapdash. The administration has had to alter its guidance multiple times after key programs were defunded in the total purge carried out on foreign aid, reinstating or exempting that particular spending from the cuts. Those who support this push argue that DOGE is merely doing zero-base budgeting (ZBB), a common process in the private sector, seeking to fix the major issues at USAID. As someone who is intimately familiar with ZBB from my past experience as a CPA, auditor, and entrepreneur, I am a fan of the process – but only when it is carried out appropriately. Normally, the ZBB process starts in advance of the next fiscal year’s budget, forcing all aspects of an organization to advocate for and defend their spending proposals from the prior year. If spending is indefensible, it is slashed from future budgets. This would work well for USAID, but the manner in which it is being implemented is entirely wrong. You don’t simply stop all funding immediately and start from the beginning while you’re in the middle of a fiscal year, especially when it comes to government work. The chaos created is not only unhelpful in understanding where to make cuts, but also hurts our reputation abroad.

If we want to implement ZBB in the federal government, there are two important things to do – neither of which DOGE is doing. First would be to center the process where the actual power lies, which is Congress. The federal legislature controls the power of the purse, allocating spending and setting its overall levels. The executive branch can tinker around the edges when it comes to funding that is not explicitly detailed in law, but that is never going to work to actually fix our broader budgetary issues. Plus, the growth of executive power with the tacit acceptance of Congress is a bastardization of the American system and should be rectified. Focusing budgeting in its proper locus would assist in reversing this malignant trend. Second, and more importantly, the ZBB process must be prospective, not immediate. That means working to change future budgets, not slashing spending while it is going out the door. The process as it is being implemented today will only discredit ZBB for future administrations and ensure that when and if it is done, it will be done in a slipshod manner. That is not what anyone who seeks a long-term change in the federal government should want. In a major political bureaucracy, durability comes only with a well-implemented and documented process. The aid freeze is the exact opposite of that.

Instead, we should be pushing for major reforms of these programs, some of which, to be fair, the reasonable backers of the aid freeze have promoted as well. One such reform is to end USAID’s existence as an independent executive agency and instead roll it up under the State Department. This will better align our foreign policy goals with our foreign aid spending, reduce the ability for grant-making that is opposed to the policies of the elected government, and centralize our foreign policy in one locus of control. All of these would be strong positive alterations to the current manner of aid disbursement. But the only way to do this is through legislation. USAID was established by executive order in 1961, but it has been codified into law as an independent agency since then; that means the proper route to reform it is Congress, not the executive. If we actually seek real change, the legislature must do its job and legislate. That there is seemingly no serious push for such legislation at this time is an indictment of the administration’s haphazard strategy.

Another key change would be to implement a better version of the zero-base budgeting process for USAID, working prospectively instead of immediately. That would mean setting up a robust and competent auditing system that would operate year-round and investigate line items and NGOs for their alignment with American foreign policy objectives. This would be the basis for the ZBB process, allowing key decisionmakers to have access to the best possible information by which to make their decisions on what to cut and what to keep. This would be a much more considered process than the current one and would actually result in far more stable and durable change in the foreign aid bureaucracy. If these officials understand that their actions and grants will be scrutinized annually in a robust and consistent process, they will be far less likely to engage in malicious noncompliance; the current aid freeze will only keep them on their toes for a short period of time before they are back to business as usual.

The last major reform should be to take a page out of the playbook of an administration often maligned by both Republicans and Democrats: the George W Bush presidency. This is oft-forgotten by those who would prefer to focus on the War on Terror and the Great Recession, but Bush created the most successful foreign aid program in American history: PEPFAR. The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, first proposed in the 2003 State of the Union address, has sent billions of dollars to Africa and the Caribbean to treat, prevent, and combat the spread of HIV and AIDS. That program has saved more than 25 million lives in two decades by providing free antiretroviral treatment and resources for prevention; those medications have allowed more than 5 million babies to be born HIV-free to HIV-positive mothers, an incredible success story. It has also reduced the transmission of this deadly virus across international borders, built significant new medical infrastructure in regions of sub-Saharan Africa that had never seen a hospital, and allowed American health officials to surveil pandemic outbreaks in Africa, stopping them before they reach a global scale.

There are several lessons to be learned from this amazing program. First, we should focus on delivering concrete material benefits to the nations and peoples to which we send our foreign aid. Saving lives from AIDS and building physical infrastructure will last generations, impacting hundreds of millions of people across a geopolitically-key region. Funding LGBTQ dance workshops is not a substitute for improving the everyday lives of real people. We should slash the former and double down on the latter. Second, PEPFAR relies very little on foreign multilateral organizations – essentially slush funds for wealthy dictators – to deliver its lifesaving aid. It is a fully American program that has consistent internal controls and direct scrutiny from policymakers. The NGOs it works with are heavily vetted and focus their activities entirely on delivering the services that the government is contracting with them for. And it is supervised by the State Department.

PEPFAR shows the way for us to regain our comparative advantage in the foreign aid game: focusing on concrete and durable improvements to local lives, cutting out wasteful spending through targeted audits and budgeting reform, running the program in-house instead of outsourcing, and closely supervising it for results. This is how we can compete with our adversaries non-militarily, build a lasting bloc of support in the developing nations that will only grow in economic and political influence in the future, and enhance our global reputation as the ‘good guy’ in a contest with the malign autocracies in Beijing, Moscow, and Tehran.

We cannot, however, implement these reforms if we are purely dedicated to an anti-left revolution, consequences be damned. Foreign aid is necessary to retain our status as the arbiter of the global order – something that we must do if we seek to remain prosperous and safe. It is but a pittance when compared to the wasteful spending and fraud here at home and, if better targeted, can deliver immense bang for the buck. Freezing this entire system in a quixotic quest to do some bastardized form of zero-base budgeting (at best) is entirely counterproductive. It will entrench opposition to much-needed actual reforms, inadvertently eliminate programs that serve our national interests, and aggregate undue power to the executive branch that will surely be abused by future presidential administrations – including the progressives the MAGA folks claim to hate. In short, it will fail miserably at achieving the ends it seeks: aligning foreign aid with foreign policy.

To use an analogy that father-of-12 Elon Musk would surely understand, it would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater. And that’s never a good idea.